What’s My Business Worth? – Part III

This is Part III in a series devoted to taking the mystery out of business valuation. In previous episodes, we covered some of the basic concepts of business valuation, and the three basic approaches to business valuation analysis. In this episode, we are going to look at how we use discounted cash flow analysis to estimate the value of a future stream of cash flows.

This presentation contains general information about the valuation process, however it is not intended to give you advice about your own particular situation. You should always consult with your own advisors and should engage a qualified professional to assist in any valuation assessment.

You can watch our latest video presentation or read on your own below.

Time Value of Money (Present Value)

Common sense tells us that cash to be received sometime in the future is worth less than cash in your hand today. Why? It’s all about risk. There is the risk that you will never realize the expected future cash flow. Remember Wimpy? “I’ll gladly pay you on Tuesday for a hamburger today.” Unfortunately, he never specified which Tuesday. Realization of that cash flow could only be described as “iffy.”

Anyone who has ever had a variable rate loan has experienced interest rate risk. As we will see in a minute, bond investors accept interest rate risk when they buy a bond. The value of their investment will fluctuate with market interest rates.

Opportunity cost is a way of saying that we have alternative uses for our cash: we could invest it in this opportunity, in another, sit on it, or spend it.

Discounting is the mathematical technique we use to measure and account for risk.

Example – Bond Valuation

A treasury bond is the classic example of a financial instrument with zero credit risk. Whether or not that is still true is beyond the scope of our discussion today, but let’s assume that it is. Let’s say we could buy a bond today for $10,000 that will mature in one year and repay our investment plus 5% interest. How much will we receive? We will receive our original principal plus the interest earned on our investment. The interest earned is simply our investment amount ($10,000) times the interest rate (.05)

Some Key Definitions:

- Future value(FV) – is the amount we expect to receive sometime in the future.

- Present value(PV) – the amount we will invest today to receive the future value.

- Discount rate(R) – the implicit interest rate that we use to calculate present value

On to the math:

Finance, like physics, is really a field of applied mathematics. I’ll try to keep the math as simple as possible, no more than high school algebra.

As we saw on our bond example earlier, the future value is the present value plus interest earned over the period of investment. Expressed as an equation, , where I = the interest earned over the period of investment. The amount of interest earned in one period is equal to the interest rate times the principal amount of the investment.

.

Substituting the PV times R for I in the first equation, we get which we can simplify to

.

From our example, investing $10,000 at 5% for one year we get 10,000 * 1.05 = 10,500. Looking at it the other way, the right to receive $10,500 in one year is worth $10,000 today.

Compounding Interest

Suppose we invested $10,000 earning 5% for 2 years? Here we see the effect of compounding.

At the end of year 1, we have , which we re-invest for another year. At the end of year two we would have earned interest on our re-investment amount giving us:

.

We can generalize the equation for compounding as follows: where n is the number of compounding periods. Dividing both sides of the equation by

, we solve for present value:

.

Using our treasury bond example, we expect to receive $11,025 in two years. The market interest rate is 5%, that is we would expect to receive 5% on a different investment with the same risk over the same term. Going through the calculation, you can see that the present value is our original $10,000.

-

where FV = $11,025, R = 0.05 and n = 2

- PV = (11,025) / (1.05 X 1.05)

- PV = 11025 / 1.025

- PV = $10,000

Interest Risk Illustrated

Now let’s suppose we are looking at a bond that was sold with a coupon rate of 5% which will pay $11,025 in two years, but in today’s market similar investments are earning 6%. How much is this bond worth?

We perform the same calculation as before, using a 6% discount rate

-

where FV = $11,025, R = 0.06 and n = 2

- PV = (11,025) / (1.06 X 1.06)

- PV = 11025 / 1.1236

- PV = $9,812

and arrive at a present value of $9,812. This says we could invest $9,812 for 2 years at 6% and will have $11,025 at the end, the same as this bond. Remember when we mentioned interest rate risk earlier? This is an example of interest rate risk. If we had paid $10,000 for this bond earlier, and wanted to sell it now it is only worth $9,812, the difference ($188) is due to interest rate fluctuations.

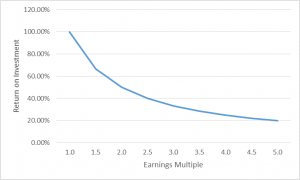

Selecting a Discount Rate

The choice of a discount rate is similar to the analysis we went through in the last program to select an earnings multiple. It involves assessing operating risk, that is how much uncertainty surrounds earnings forecasts. It also involves macroeconomic forecasts of future interest rates, and comparing with expected returns associated with alternative uses of investment funds.

There are a number of factors to consider in evaluating operational risk. Let’s take a look at a few of them:

Revenues: Obviously revenues, or sales, is important, as revenues are the source of profits. Level of revenues is important, but we should also consider trends in revenues: is it growing year over year, stagnant, or declining? How does this company’s revenue levels compare with other, similar companies?

Predictability of Revenues: How likely is it that future revenues can be estimated based upon past revenue levels? If a company relies on a few, major customers, it is much riskier than a company that has a large, diverse customer base. The loss of even one major customer could change a profitable company into a loser. Repeat business, or business coming from referrals of past customers is an indicator of customer satisfaction with the company and its products or services. Looking at accounts receivable collection history can give us a perspective on the quality of customers. High bad-debt write-offs indicate a high-risk customer base. After all, a sale is only a sale when cash is received.

Earnings: When someone buys or invests in a business, what they really are buying is the future stream of cash flows or profits. We should look at profit margins, return on sales and return on investment, to evaluate the business performance and compare it with its peers. What are the trends in profits? A consistent trend of increasing profits would justify a lower discount rate than a level or declining profit trend.

Competitive Environment: Understanding the competitive environment is critical to evaluating the risk to the company’s profit trend. How likely is it that a new competitor will enter the market? Are there any barriers to entry that would make it more difficult for a new competitor. Is there something unique about the business being evaluated. How does the company position its products or services? Is it a premium product, or a discount brand?

Reliance on the Owner: Does the company have written procedures and processes, or are they carried around in the owner’s head? Are customers and suppliers loyal to their relationship with the owner, or to the company’s products and services. Is there a management team in place to operate the business in the owner’s absence. Could a buyer expect that the owner will be cooperative during the transition? In a sale, is the owner willing to partially finance the deal?

Discounted Cash Flow Method:

There are four major steps in performing a discounted cash flow analysis:

- First we project future earnings, typically over 5 years but it could be longer or shorter.

- Estimate a selling price for the business at the end of the projection timeline.

- Determine an appropriate discount rate. The discount rate represents a risk-adjusted opportunity cost of capital for a prospective buyer or investor.

- Calculate the present value of the projected cash flow stream.

Example Discounted Cash Flow Analysis

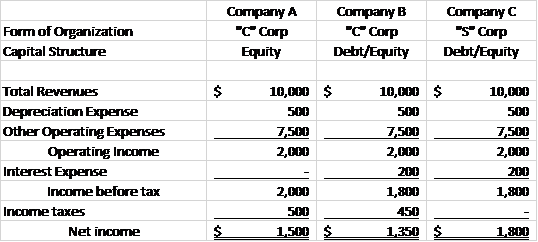

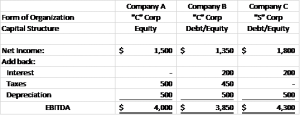

Let’s perform the four steps based on the data in Figure 1 above:

- We’ve prepared a five-year projection of earnings for our example company. In the first year, we expect $10,000, and we expect earnings to grow by 6% per year thereafter.

- Based upon forecasted year 5 earnings, we expect to sell the company at the end of year 5 for $34,719. The total cash received column is simply the yearly earnings added to the proceeds of sale.

- We have chosen a discount rate of 35%. As we discussed in our previous article, investment in a small business is significantly more risky than investing in the stock market, bond market, or real estate. The 35% is based on our best estimate for risks associated with the projected future cash flows.

- We then divide each year’s cash receipt by the discount rate to get the present value of that year’s cash flow. Note in year 2, the discount rate is 1.035 X 1.035.

We sum up the present values and arrive at a valuation estimate of $31,934.

Summary

To summarize, expected cash flow in the future is less valuable than cash-in-hand today. We use discounting as a technique to estimate the value of expected future cash flows. In the discounted cash flow method, we estimate future cash flows, and discount using a risk-adjusted discount rate to arrive at the present value.

I hope this has been informative. In the next installment, we’ll cover financial statement analysis. Then we’ll put it all together with a valuation analysis of an example company.

Cypress Business Partners offers a free estimate of the value of your business. Please let us know how we can be of service to you. Visit us on the web, or on Facebook. If you would like to be informed when the next presentation is available, please send me your email address. I promise to respect your privacy and will never share your information with anyone.